Web APIs and Integration Testing with Mocks

Today's in-class code is in the repository, within the S25/feb6_nws_api folder. Please pull the repository and make sure you can load this. Remember to load the pom.xml file as a project. This will tell IntelliJ to import dependencies, etc. for the project. If you open as a folder or file, IntelliJ won't auto-configure the project.

Anticipating that some of you will want to add logging to a file whenever your server receives a request, I made this proof-of-concept example that shows how to set up logging actions before handlers are invoked.

Today's in-class exercise is here.

Looking Ahead!

In next week's sprint, 2.1, you'll be building a server that listens for and responds to requests. It gets its data from your CSV files. In 2.2, you'll also be getting data from other servers on the Internet. We anticipate some of the major challenges to be:

- setting the server up to listen properly (you'll use the strategy pattern for this, because that's how the web-server library we use is engineered);

- serializing and deserializing data to and from other servers; and

- limited caching of prior results (you'll use the proxy pattern for this!).

For testing: You'll be using Postman to write example API queries to exercise your API. For now, we won't automate inspecting the responses, but we will get there in time.

Readings

Your readings for this sprint include:

- Bloch (Effective Java)

- Minimize mutability (Item 17);

- Check parameters for validity (Item 49);

- Make defensive copies when needeed (Item 50);

- Some of the items about exceptions (Items 69, 70, 72, 73, and 75);

- This short article about Internet access; and

- This page about the Equitable Internet Initiative.

Some of these reinforce concepts from class; others introduce deeper discussion than we have time for (e.g., much of the exceptions content). You're of course free to read more of Bloch if you wish; we strongly recommend it for learning about OO Java programming.

We will have another class on generics in the future, and Bloch's Item 31 would be a good companion to that.

Livecode

The code for today supplements the gearup example you'll get on Monday. We'll talk about:

- invoking (and creating) Web APIs; and

- using "mocks" to avoid several different costs in development.

This example does not cover caching, which you'll need for the sprint. For that, see the previous livecode. Although it does have an empty class that demonstrates the shape.

Web APIs

There's a lot of useful information out there on the web.

One way we might work with that info is to scrape websites: write a script that interacts with the HTML on a webpage to extract the info.

Why Not Web Scraping?

What are some weaknesses of web scraping, from the perspective of both the person doing the scraping, and the person who is running the website?

Think, then click!

A few issues might be:

- The owner of the data might want to charge for access in a fine-grained way, or limit access differently from the way it works on a webpage.

- Web scraping is unstable. If a site's format changes, web-scraper scripts can break. APIs can have breaking changes too, but when they do, the changes usually come with a warning to users!

- Web scraping is mostly a one-sided effort. While a site designer might work to ease the job of web scrapers, details can still require some guesswork on the part of the script author.

It turns out that ideas from web-scraping will remain useful though, when we get to testing front-end applications in a few weeks.

Web APIs

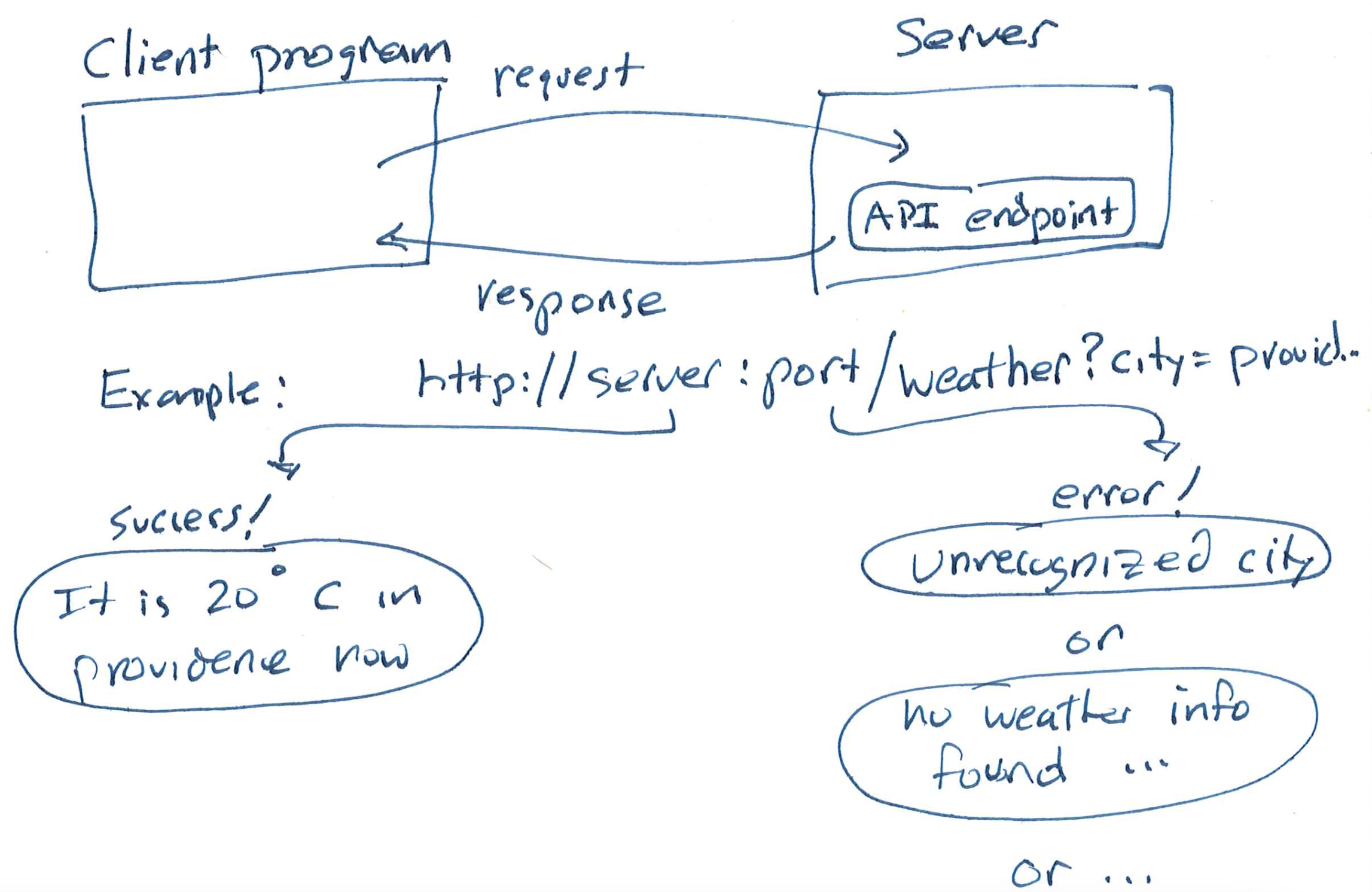

APIs work like this: the user sends a structured request to the API, which replies in a documented, structured way. API is short for Application Programming Interface, and often you'll hear the set of functions it provides to users called the "interface".

This is an example of an "interface" in the broad, classical sense. It isn't a Java interface. It's one of many ways for two programs to communicate across the web, but it's specific and well-defined.

APIs are everywhere. Whenever you log in via Google (even on a non-Google site) you're using Google's Authentication API.

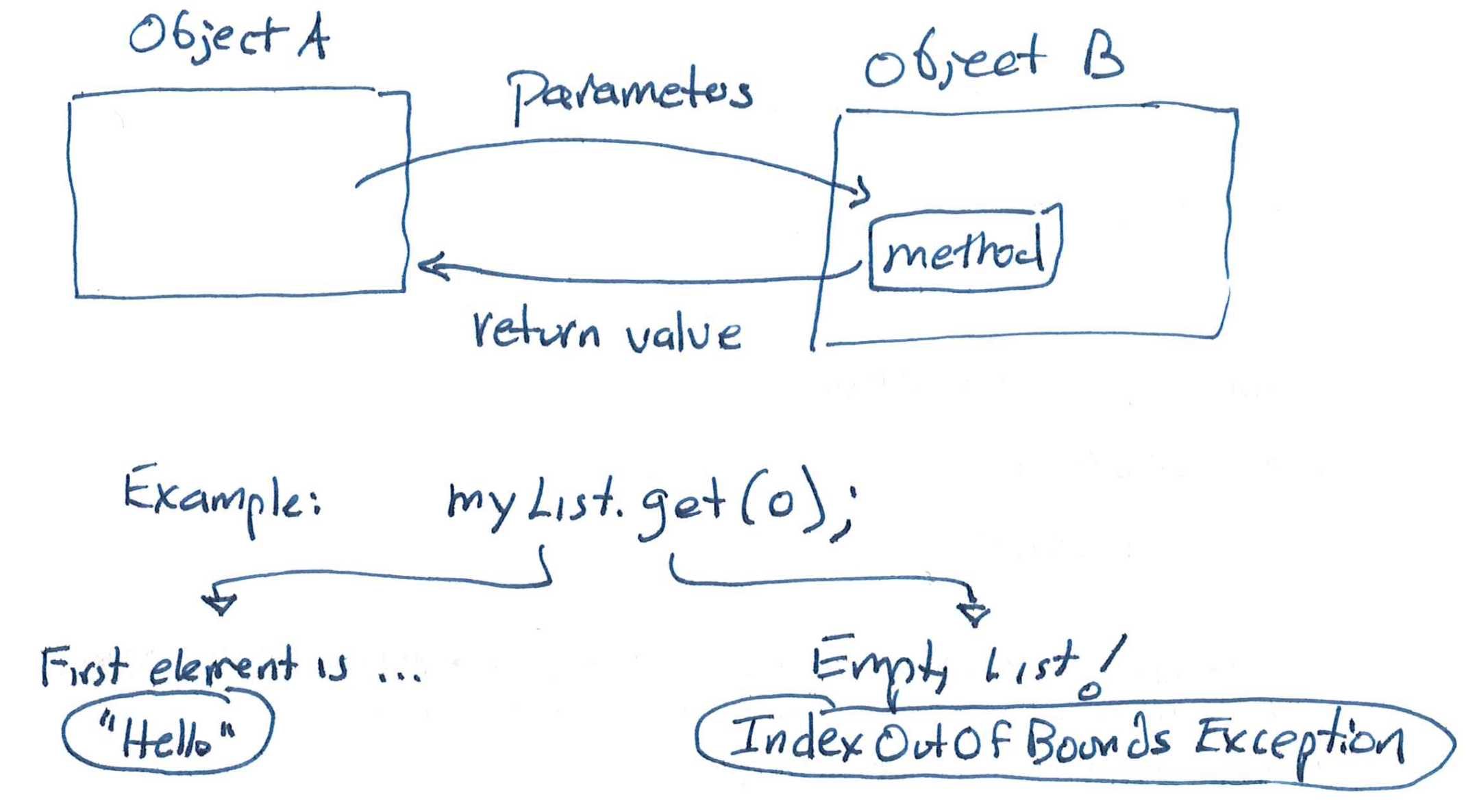

APIs are very like method calls! The pictures are very similar:

The differences are in the ways we go about making a call (and processing the result). E.g., we have to build a request string that embodies the call, and we have to turn the response object into usable data.

Example: National Weather Service

Let's start right away with a serious, high-volume API: the U.S. National Weather Service. These APIs tend to be well-documented. We'll use the NWS because, while many professional APIs require registration and the use of an API key to use them, the NWS API is free and requires no registration.

The NWS API is not the exact API you will be using on the sprint, but I like it for demonstrating the same kind of interaction you'll need to implement.

Let's get weather information for Providence. Our geocordinates here are: 41.826820, -71.402931. According to the docs, we can start by sending a points query with these coordinates: https://api.weather.gov/points/41.8268,-71.4029:

Queries

There are a few things to notice right away. First, the URL we sent had a host portion (https://api.weather.gov) and an endpoint (called, confusingly, points) that represents the kind of query we're asking. Then there are parameters to the query (41.8268,-71.4029).

Because last year, the API would give an error if we tried to provide 6 significant digits. So we truncate.

Responses

We get this back:

{

"@context": [

"https://geojson.org/geojson-ld/geojson-context.jsonld",

{

"@version": "1.1",

"wx": "https://api.weather.gov/ontology#",

"s": "https://schema.org/",

"geo": "http://www.opengis.net/ont/geosparql#",

"unit": "http://codes.wmo.int/common/unit/",

"@vocab": "https://api.weather.gov/ontology#",

"geometry": {

"@id": "s:GeoCoordinates",

"@type": "geo:wktLiteral"

},

"city": "s:addressLocality",

"state": "s:addressRegion",

"distance": {

"@id": "s:Distance",

"@type": "s:QuantitativeValue"

},

"bearing": {

"@type": "s:QuantitativeValue"

},

"value": {

"@id": "s:value"

},

"unitCode": {

"@id": "s:unitCode",

"@type": "@id"

},

"forecastOffice": {

"@type": "@id"

},

"forecastGridData": {

"@type": "@id"

},

"publicZone": {

"@type": "@id"

},

"county": {

"@type": "@id"

}

}

],

"id": "https://api.weather.gov/points/41.8268,-71.4029",

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [

-71.402900000000002,

41.826799999999999

]

},

"properties": {

"@id": "https://api.weather.gov/points/41.8268,-71.4029",

"@type": "wx:Point",

"cwa": "BOX",

"forecastOffice": "https://api.weather.gov/offices/BOX",

"gridId": "BOX",

"gridX": 64,

"gridY": 64,

"forecast": "https://api.weather.gov/gridpoints/BOX/64,64/forecast",

"forecastHourly": "https://api.weather.gov/gridpoints/BOX/64,64/forecast/hourly",

"forecastGridData": "https://api.weather.gov/gridpoints/BOX/64,64",

"observationStations": "https://api.weather.gov/gridpoints/BOX/64,64/stations",

"relativeLocation": {

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [

-71.418784000000002,

41.823056000000001

]

},

"properties": {

"city": "Providence",

"state": "RI",

"distance": {

"unitCode": "wmoUnit:m",

"value": 1380.4369590568999

},

"bearing": {

"unitCode": "wmoUnit:degree_(angle)",

"value": 72

}

}

},

"forecastZone": "https://api.weather.gov/zones/forecast/RIZ002",

"county": "https://api.weather.gov/zones/county/RIC007",

"fireWeatherZone": "https://api.weather.gov/zones/fire/RIZ002",

"timeZone": "America/New_York",

"radarStation": "KBOX"

}

}

This wasn't nicely formatted for human reading. Why? Because it's meant for programs to consume. This string should bear a remarkable resemblance to TypeScript objects. It's called Json: JavaScript Object Notation. When we write programs that work with web APIs, we'll never manually parse these, we'll use a library that does it for us. In general:

- when we're converting data or an object in our program to a format meant for transmission (like Json) we'll call it serialization; and

- when we're converting a transmission format (like Json) into data or an object in our program, we'll call it deserialization.

What else do you notice about this data?

Think, then click!

One thing is: you can ignore a lot of it. This first query gives us useful information for further uses of the API. Another is that there's no actual weather information here...

See the documentation to understand the meaning of specific fields in the response. At a high level, this query tells us which NWS grid location Providence is in, along with telling us URLs for common queries about that grid location. The NWS API needs you to work with it in stages.

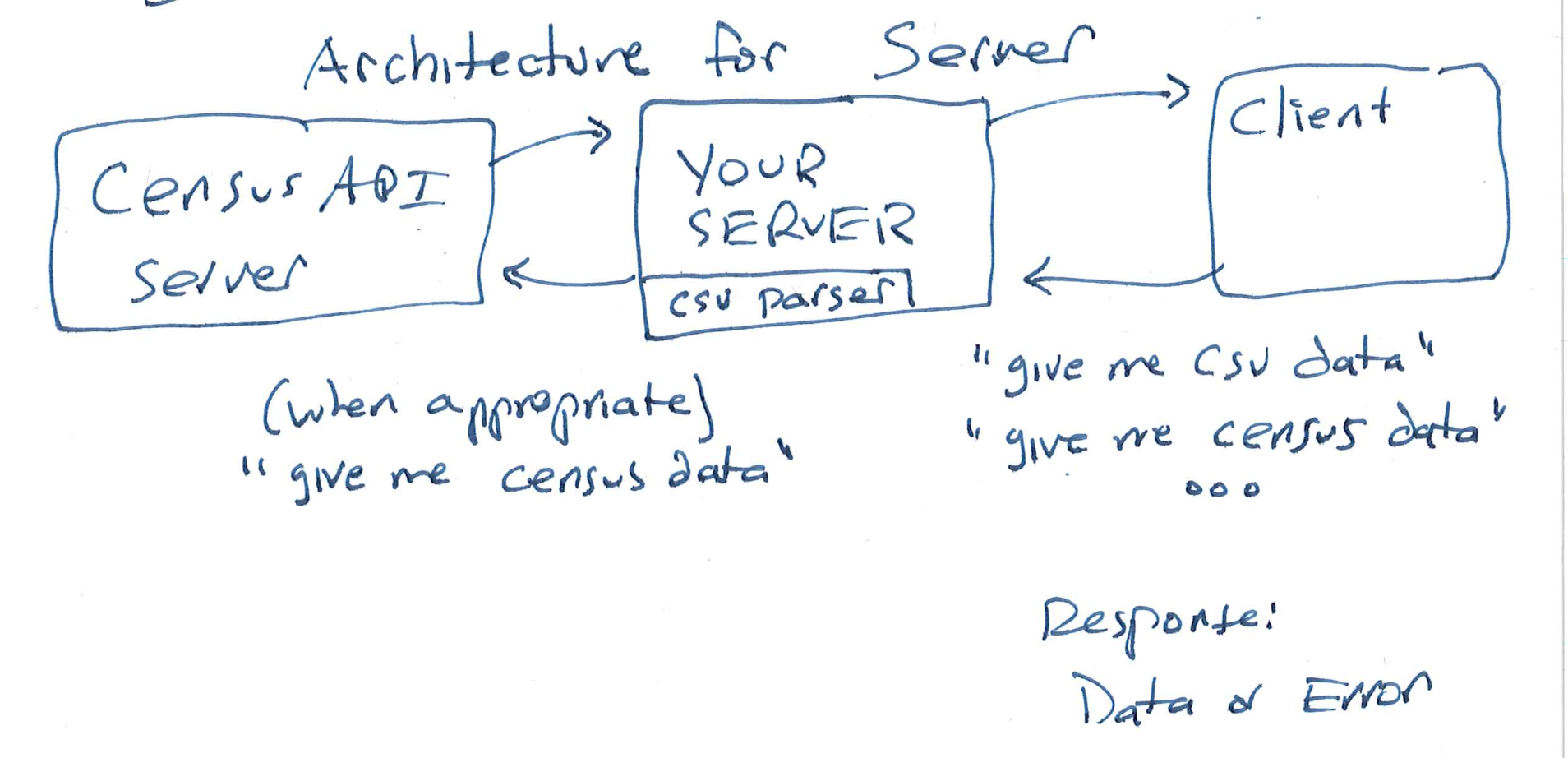

Building API Servers

The livecode example is an API server that sends requests to another API server:

- Someone sends our API server a request for the weather at a certain geolocation.

- Our API server asks the NWS what their grid coordinates are for that geolocation.

- Our API server asks the NWS for the forecast at that location.

- Our API server responds to the original request, reporting the weather forecast.

Setting up a server

We'll use a library called Sparkjava to run our API servers. Sparkjava is relatively simple to set up: we just tell it which port to use (here, 3232), which endpoints to listen at, and for each, a handler object (there's the strategy pattern again!) that processes requests.

If you Google for 'spark', you're likely to get answers related to Apache Spark, a more popular library that happens to be for data science, not web servers. Watch out!

In the livecode for today, you'll see the entry point in the Server.java file. The code looks something like this:

private final WeatherDatasource state = new NWSAPIWeatherSource();

Spark.port(port);

Spark.get("/weather", new WeatherHandler(state));

Spark.awaitInitialization();

In this case, the WeatherHandler object's constructor takes a data source object. Why do you think that is?

Think, then click!

Extensibility and testing! If we added more handlers, we'd probably need to share some state between them. This sort of dependency injection allows us to do just that. We might even wrap the datasource in a class that holds other kinds of state or other data sources.

Each of these handler classes handles queries sent to a specific endpoint. Here, queries to weather are handled by a WeatherHandler object.

You might notice that the data source being created is a NWSAPIWeatherSource, but it's being used only by an interface, WeatherDatasource. This enables some very useful techniques, including better testing.

Testing API Servers: Example of Integration Testing

Our philosophy is generally that you'll be able to test most everything you do, so as you start work on the Server sprint, you should be asking: how can I test my API server?

One way is to write unit tests. E.g., if we have a CSV data source (hint: you do!), we should have unit tests for that. If we have a source that goes to the National Weather Service to fetch forecasts, we should test that.

But neither of those will test the server. How can we do that? We need to test the combination of a number of units: the code that accesses the data source, code (if any) that processes the raw data, the API handlers of our server... When you're testing the integration of multiple components in your application (such as our server tests) this is called integration testing.

One way, which is what we did in prior semesters, is to write a test class that starts up our server locally, sends it web requests, and evaluates the response—all done on the local computer, no Internet connection needed. In Spring 2025, we're instead using a tool called Postman, which can help us script API requests and examine responses. For the moment, we'll just use it as a library of example queries that we can manually inspect results for.

Mocking (a remarkably powerful technique)

Consider what happens when I run integration tests, whether we're rolling them manually in Java or using Postman. These generate web requests to our server, and then (assuming normal operation), our server will send a series of web requests to the NWS API.

This is reasonable, but has a number of problems. What issues have I introduced into my testing because running the tests requires the NWS API?

Think, then click!

At the very least, the more I test (and I should test often!), the more I'll be spamming the NWS with requests. If I do it too much, they might think I am running a denial-of-service attack on them, and rate limit my requests. I also just can't run my test suite without an Internet connection, or if the NWS is down for maintenance.

(There are other reasons, too.)

Hence the MockedNWSAPISource class, which implements the same interface that the real data source class does. Instead of getting me the real forecast, however, it always returns a constant temperature. No NWS needed.

You'll use mocking in every sprint from now until the class is over; we've only barely discovered how important it is as a technique. And the patterns we have learned so far are perfect for implementing mocking well. To start with, a data source can be a strategy provided by the caller (real or mock).